Dear Reader,

Since Donald Trump’s re-election in November 2024, his favourite word—“tariff”—has morphed from a campaign threat into a cornerstone of US economic policy.

As of 6th April 2025, the US has placed a 20% “reciprocal” tariff on all EU goods, alongside 25% tariffs on steel and aluminium and 10% on cars. The effects are already evident: bond yields have fallen by over 0.5% since these policies took effect, a sign that markets fear an economic slowdown. But why would the US deliberately “crash” its economy in this way? Is this as “stupid” and short-sighted as some commentators believe and suggest, or is there a deeper strategy at play—one that goes beyond the whims of a president eager for deal-making at any cost?

A Strategic Gamble: Tariffs as Tax Revenue?

My theory is that the Trump administration aims to generate vast amounts of tax revenue in an electorally palatable way. The Congressional budget office (CBO) estimates that a 10% baseline tariff on imports could raise $200 billion (£157 billion) annually, but with Trump’s announced tariffs reaching as high as 46% on some goods (e.g., Chinese imports), the revenue could be far greater—potentially $500–600 billion (£392–471 billion) per year, according to some analysts. Consider the tax the CBO calculated from just a 5% rate.

This windfall could fund tax cuts or infrastructure spending, appealing to Trump’s voter base while avoiding the political fallout of domestic tax rises.

But there’s a broader context I believe: The spiralling US national debt. Over the past 12 months, the gross national debt has risen by $5,308 (£4,167) per person, or $13,446 (£10,557) per household, bringing the total to $108,137 (£84,900) per person and $273,921 (£215,073) per household. With an annual deficit of $1.8 trillion (£1.4 trillion), the US government may be growing nervous about the sustainability of this trajectory. Tariffs offer a way to raise revenue without directly taxing American citizens, but of course it comes with risks—higher consumer prices, disrupted supply chains, and potential retaliation from trading partners.

Is the calculation not that the reward outweighs the risk?

Another threat to the US is the wildcard role of foreign holders of US debt, particularly China, which holds about $1 trillion (£785 billion) in US Treasury securities. A massive sell-off by China could destabilise the economy by triggering an avalanche of selling from other investors.

Stoking the demand for bonds is a way to forestall this. A proactive measure and will we see more? We know US tax cuts are coming, don’t be surprised to see taxes that encourage Americans to invest in Treasuries. These are already excluded from any City and State taxes, will we see a move on Federal tax too?

Moody’s said America’s triple-A grade increasingly relies on “extraordinary economic strength and the unique and central roles of the dollar and Treasury bond market in global finance.”

Let’s not forget too the impact of the asset grab by the West of Russian assets in 2024. The “rules-based” West. Except they broke the rules. Seizing the assets, no matter how you feel about Ukraine and Russia and Putin, was arguably wrong. Regardless of the morality it broke the rules. I’m surprised Trump doesn’t call that out about Biden. Perhaps he should read the Oak Bloke.

DOGE $140bn Savings

If these savings are to be believed DOGE has already reduced costs equivalent to 7% of the US budget deficit. There is a healthy amount of scepticism from the press and scrutinisation which actually makes me believe that that number is fairly solid. When will the UK get a DOGE?

In 2029 perhaps? If the US powers through to prosperity then this is a compelling and I believe unstoppable electoral message whichever party or parties adopt it. Who knows perhaps PM Starmer shall?

Or who knows if Canada doesn’t want to be the 51st State then maybe we will get the chance? Go on reader, vote for or against that idea.

US ECONOMICAL REFORM

Trump meanwhile is engaged in extensive supply-side reforms, such as more energy production, deregulation, and spending cuts. These measures could and I believe will spur growth and expand the tax base. That would also lower inflation, allowing the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates and ease borrowing costs.

It’s early days and of course the Sentiment is bad, but what is the actual evidence so far?

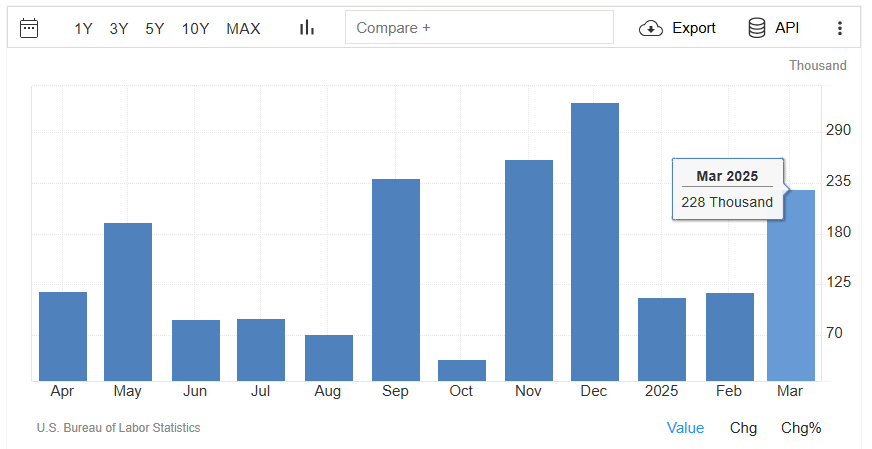

On Friday the US jobs report announced 228k new jobs (estimate 135k) so that’s some evidence that doom and gloom isn’t the order of the day in the US. But no evidence that DOGE is slicing through wasteful government employment either.

GDP forecast

The NIESR calculated that retaliation will slow US GDP growth by 0.5% in 2025 and 0.7% in 2026, respectively. So worst case US GDP will be 1.2% in 2025 and 1.4% in 2026.

They go on to say Global GDP growth “could” weaken by 2% over five years so 0.4% a year.

Global GDP growth is projected to be 3.3% in 2025 and 3.3% in 2026, according to the OECD, slightly above the 3.2% growth in 2024. So it will fall to 2.9% instead of 3.3%

Do those numbers justify panic? It is a rhetorical question.

US Corporate Profits are sharply up 5.9% up in the latest (4Q24) results.

US New Orders are very robust.

US Investment (Fixed Capital Formation) is down a touch but also very robust.

US Exports are 11% of US GDP. So 89% is not directly unaffected.

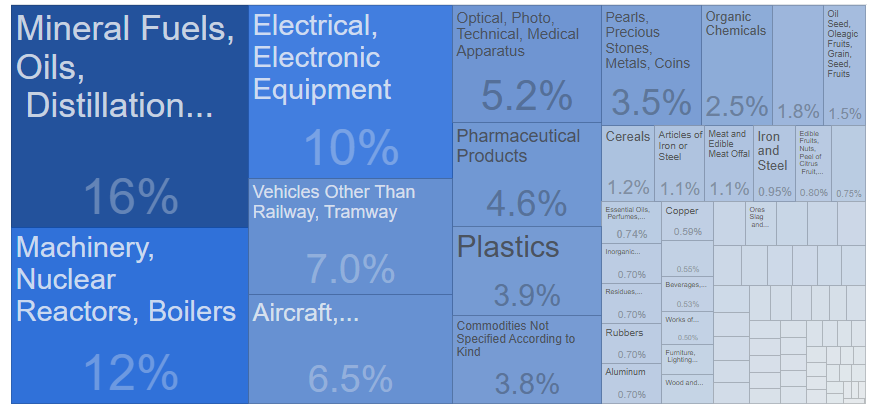

These are the US Exports countries so you can consider those subject to counter tariff. The EU is 3.4% of US GDP, China 1.7% of GDP.

These are the goods exported. Predominantly Fuel and Capital Goods. Taxing those would disadvantage EU and Chinese business.

US Exports are at record levels.

The EU’s Dilemma: Retaliation with Risks

The EU, alongside countries like Germany and France, have already responded with countermeasures, announcing tariffs on up to £22 billion of US goods in March 2025, targeting products such as bourbon whiskey, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, and soybeans. A proposed 50% tariff on bourbon has sparked internal debate, with France lobbying for its removal to protect its wine industry from US retaliation. The EU is also considering its Anti-Coercion Instrument, which could restrict US companies’ access to EU markets, such as revoking banking licences for firms like J.P. Morgan or blocking US tech giants from public procurement contracts.

However, retaliation is a double-edged sword. Consider the US’s top exports: crude petroleum ($125 billion, £98 billion), refined petroleum ($107 billion, £84 billion), petroleum gas ($83.2 billion, £65 billion), gas turbines ($69.3 billion, £54 billion), and cars ($65.3 billion, £51 billion). Tariffs on these goods would drive up energy and equipment costs in the EU, directly harming its own economy. The US also has a significant services surplus, with top exports like personal travel ($158 billion, £124 billion in 2018), business services ($130 billion, £102 billion), and financial services ($114 billion, £90 billion) proving far trickier to tax without disrupting global markets. The US likely calculated this asymmetry: any EU counter-tariff risks being self-inflicted pain, a fact that strengthens America’s negotiating hand.

Moreover, the EU’s claim of low tariffs isn’t as clear-cut as it seems. Before Trump’s first term, the EU imposed Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariffs averaging 5.1%, but agriculture faced much higher rates—12.2% on average, with dairy at 35.4% and cheddar cheese at 50%. Cars faced a 10% tariff, compared to the US’s 2.5% (though the US charged 25% on EU pickup trucks). Non-tariff barriers, such as the EU’s ban on hormone-treated beef since 1989 and chlorine-washed poultry since 1997, have long restricted US exports, costing American farmers billions annually. The EU also uses regulations like GDPR, implemented in 2018, as a non-tariff barrier, raising compliance costs for US tech firms and arguably stifling fair competition. With 27 member states often horse-trading over pet projects, EU trade policy can be as protectionist as the US claims—though the EU frames it as consumer protection.

The UK’s Precarious Position: Impacts and Risks

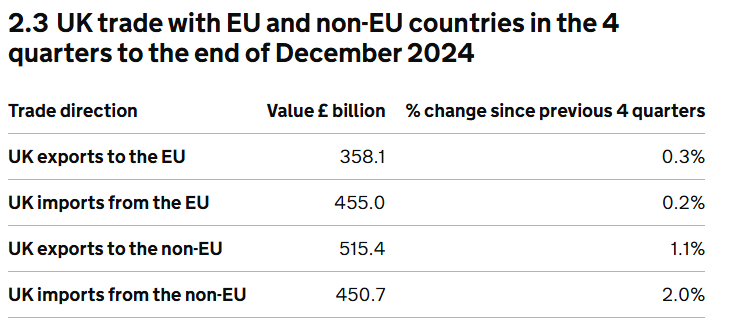

A tariff is generally imposed on goods not services. Services are and have been the mainstay for the UK and remain so. Service exports have nearly doubled in 10 years.

Our trade with the EU is increasing and relations are warming. For whatever else he’s done Starmer appears to be doing a reasonable job in that.

Consider that the UK’s acession to the CPTPP trans-pacific treaty eliminates 99% of tariff lines between members and while people poo-poohed its impact do not forget that it is the destination for our #12, #14, #17, #18 largest exporters and the bloc represents 14.4% of world GDP.

Consider too that the CPTPP is growing and will grow. Will the move by Trump actually drive other countries to seek free trade with new partners?

China, Japan and South Korea strengthened a free trade agreement Sunday 6th April in response to US Tariffs.

CPTPP applicants:

Here in the UK, the government is charting a different course, preparing for a £32 billion spending surge starting in April 2025. This fiscal boost, outlined in Reeves 2024 budget, aims to address domestic priorities amidst global trade turbulence:

NHS Funding: £22.6 billion over two years (£11.3 billion in 2025/26) for capital investments like hospitals and equipment, plus £1.5 billion for operational costs, including 2% above-inflation pay rises. Total health spending will reach £214.1 billion, reflecting the UK’s commitment to bolstering its healthcare system post-COVID.

Education: £6.7 billion in 2025/26, with £4 billion for schools (e.g., teacher recruitment) and £2.7 billion for early years and childcare expansion, addressing long-standing gaps in educational access.

Local Government: £1.3 billion extra for social care and services in 2025/26, part of a £5.3 billion two-year package, aimed at supporting vulnerable populations amidst rising costs.

Transport and Infrastructure: Over £5 billion in 2025/26 for capital projects, including HS2 adjustments and road repairs, within a £100 billion five-year plan averaging £20 billion annually.

Other Investments: £1 billion for defence maintenance and £500 million for green tech, such as carbon capture, signalling a focus on security and sustainability.

While this spending surge aims to stimulate growth and support public services, the UK is not insulated from the fallout of a US-EU trade war. As a major trading partner with both blocs, the UK faces significant risks. In 2024, the UK exported £57 billion in goods to the US (primarily cars, pharmaceuticals, and whisky) and £294 billion to the EU (notably vehicles, machinery, and chemicals), while importing £85 billion from the US (including fuel and aircraft) and £340 billion from the EU (mainly vehicles and food). A full-blown trade war could disrupt these flows in several ways:

Higher Import Costs: If the EU imposes tariffs on US petroleum products, global energy prices could rise, increasing the cost of fuel imports for the UK. The UK imported £14 billion in refined petroleum from the US in 2024, and a 25% EU tariff could push prices up by 5–10%, adding £700 million annually to import costs, according to estimates from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

Supply Chain Disruptions: The UK relies on EU supply chains for manufacturing, particularly in the automotive sector. EU tariffs on US cars and components could raise costs for UK manufacturers like Jaguar Land Rover, which sources parts from both regions. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) warns that a 10% cost increase could reduce UK car production by 50,000 units annually, risking 10,000 jobs.

Export Challenges: The US is the UK’s largest single-country export market. A broader US tariff escalation—say, extending the 20% EU tariff to the UK—could hit British exports like whisky (£1.2 billion annually) and cars (£7 billion). A 20% tariff could reduce UK exports to the US by £5 billion, per Oxford Economics, dampening growth in key sectors.

Inflation and Consumer Impact: Higher import costs would feed into consumer prices, exacerbating inflation, which stood at 2.3% in the UK in March 2025. The Bank of England has already cautioned that a US-EU trade war could shave 0.5% off UK GDP in 2026, potentially forcing interest rates higher and squeezing household budgets further.

The UK’s £32 billion spending surge could cushion some of these impacts by boosting domestic demand, but it also increases borrowing at a time when global economic uncertainty is rising. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) projects that UK public sector net debt will reach 93% of GDP in 2025/26, up from 91% in 2024. A trade war-induced slowdown could worsen this, forcing the government to either cut spending or raise taxes—neither of which is politically palatable.

A UK-US Free Trade Agreement: Prospects and Benefits

Amidst these challenges, a potential UK-US free trade agreement (FTA) offers a glimmer of hope. Negotiations for a UK-US FTA have been on and off since Brexit, with talks stalling under the Biden administration due to disagreements over agriculture (e.g., US demands to lift the UK’s ban on chlorine-washed poultry) and digital trade. Trump’s return, however, has revived prospects, given his administration’s emphasis on bilateral deals over multilateral frameworks.

Prospects for an FTA: Trump has signalled a willingness to prioritise a UK deal, viewing the UK as a strategic ally outside the EU’s orbit. In February 2025, US Trade Representative Katherine Tai met with UK Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds, agreeing to “fast-track” negotiations with a target completion date of late 2025. The UK’s post-Brexit flexibility to set its own trade policy makes it an attractive partner for the US, especially as a counterweight to the EU. However, sticking points remain: the US insists on market access for its agricultural products, including hormone-treated beef, while the UK is wary of lowering food standards, a red line for British consumers and farmers. Digital trade, particularly data flows and tech regulation, is another hurdle, with the US pushing for lighter rules than the UK’s GDPR-aligned framework.

Potential Benefits:

Tariff Reductions: A UK-US FTA could eliminate tariffs on key UK exports like cars (currently 2.5% to the US) and whisky (currently 0% but at risk of US retaliation). The Department for Business and Trade (DBT) estimates that removing these tariffs could boost UK exports by £2 billion annually, supporting 20,000 jobs in sectors like distilling and automotive manufacturing.

Services Sector Growth: The UK has a services surplus with the US, exporting £33 billion in financial services, travel, and professional services in 2024. An FTA could deepen this by easing US regulations on UK banks and insurers, potentially adding £5 billion to services exports by 2030, per the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP).

Investment and Innovation: An FTA could encourage US investment in the UK, particularly in tech and green energy. The US is already the largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the UK, with £560 billion in 2024. A trade deal could unlock an additional £10 billion in FDI annually, according to UK government projections, supporting projects like battery manufacturing for electric vehicles.

Geopolitical Alignment: Beyond economics, an FTA would strengthen the UK-US “special relationship,” enhancing cooperation on issues like defence and technology (e.g., AI standards). This could position the UK as a bridge between the US and EU, amplifying its global influence post-Brexit.

Challenges and Risks: An FTA isn’t a panacea. Concessions on agriculture could spark a backlash from UK farmers, already struggling with post-Brexit trade barriers to the EU. The National Farmers’ Union (NFU) warns that allowing US hormone-treated beef could undercut British producers, costing the sector £500 million annually. Moreover, aligning too closely with the US risks straining relations with the EU, the UK’s largest trading partner. If the EU perceives the UK as a backdoor for US goods, it could impose stricter border checks, further disrupting EU-UK trade.

Conclusion - A Deeper Strategy or a Dangerous Game?

I believe the US tariff strategy is a calculated move to address its debt crisis and shift global trade dynamics in its favour, but it’s not without flaws. Higher tariffs could fuel inflation—already a concern with US CPI at 2.7% in March 2025—while alienating allies like the EU and UK, whose countermeasures could disrupt global supply chains.

The EU’s protectionist history, from high agricultural tariffs to regulatory barriers, complicates its moral high ground, but its fragmented decision-making limits its ability to respond cohesively.

The UK, meanwhile, stands to gain a Free Trade Agreement which will prove to be a boon for both the UK and US. Moreover, this also could make the UK an investment destination in the “US sphere”. Arguably even the current 10% tariff does that vs the 20% EU tariff.

Is the US strategy just about ideology? A return to economic nationalism that prioritises short-term wins over long-term stability? I don’t believe so. Trump I’ve said before is building his legacy. He wants to be the best President ever. Tackling the “Clear and Present Danger” as he sees it is what he is doing. So I believe it is actually about addressing US weakness, and reprioritising. The moves made by the US to withdraw from European defence would be a huge cost saving for the US of around $36bn per year. That’s another 2% of the US Budget Deficit removed.

Meanwhile for the UK, there is opportunity I believe.

Potentially a UK-US FTA offering tariff-free access to the US market and deepening economic ties would be enormously beneficial. However, the benefits would be a delicate balance weighed against the risks of alienating the EU and compromising domestic standards. UK Prime Minsters have navigated that balance behind the concentric circles of influence ever since 1945 and so they continue today.

Regards

The Oak Bloke

Disclaimers:

This is not advice - make your own investment decisions.

Micro cap and Nano cap holdings might have a higher risk and higher volatility than companies that are traditionally defined as "blue chip"

The UK EU loving establishment will conspire to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory over trade with the US. They are already making noises over Online Safety being a red line when it's a main purposes is a mechanism to limit free speech.

I’m not sure the American people will want tax cuts funded by tariffs (not sure they will even raise enough to cover the cost of them either) seeing as primarily they voted him in to make them better off. No matter what happens tariffs are going to increase prices for consumers in America - either due to tariffs or if any business is crazy enough to reshore their operations (which will be far more cost;y than overseas). Not everything can be onshored either as some resources are not available so they still need to come in (unless blocked by countries like China have done). Then there’s the impact to the economy from retaliatory tariffs that will hit the US economy by a potentially significant amount (already talk of huge sums to subsidise the agriculture sector). The bit trump ignored with his game show tariffs board was the biggest component of American trade, services, which they run at a surplus to the world. If other countries get smart and start to hit those then the American economy (which is rather dependent on the,) is going to really take a kicking.

As for what the UK should do there is no real simple answer other than absolutely not be part of the USA - I wouldn’t want their bonfire of regulations which are stripping out all consumer protections everywhere. Not all regulations are bad, it’s been shown time and again unrestricted capitalism doesn’t end well. Not sure they will create sustainable growth either (pretty sure the oil industry has no intention to drill baby, drill as they don’t want oversupply).

Personally I think the UK should pivot more to its biggest and nearest trading partners (Europe) and tell Donald to just F Off.